The

dynamic landscape of the Outer Banks is utterly amazing.

Tiny grains of sand, uncountable, individually insignificant,

yet all together they combine to create the fascinating

landscape of the Outer Banks. Even as tiny as they

are, each grain of sand is thousands of times larger than

the molecules of air and water which move and shape this

landscape every second of every day. These molecules are

so tiny they cannot be seen under a microscope, yet they

push the sand about in a restless frenzy, and have done

so for hundreds of thousands of years. And still these

Outer Banks remain. The

dynamic landscape of the Outer Banks is utterly amazing.

Tiny grains of sand, uncountable, individually insignificant,

yet all together they combine to create the fascinating

landscape of the Outer Banks. Even as tiny as they

are, each grain of sand is thousands of times larger than

the molecules of air and water which move and shape this

landscape every second of every day. These molecules are

so tiny they cannot be seen under a microscope, yet they

push the sand about in a restless frenzy, and have done

so for hundreds of thousands of years. And still these

Outer Banks remain.

| This

site uses GPS coordinates where applicable,

displayed in red in the decimal degrees format

(hddd.ddddd°).

As coordinates are collected, they will be

retrofitted to existing information, and incorporated

into future information. (More

info and conversions) |

|

This is a continual and natural

process. Wind and currents keep the sand moving, slowly

washing away from one area, only to be piled up in another

area, changing the contours of the shoreline. This process

also changes the depth of the water, both in the ocean

and the sounds. The channels which connect the sounds

to the ocean, allowing water and sea life, and boats,

to move between the ocean and shallow protected sounds,

are called "inlets". These inlets also constantly change

shape and depth.

|

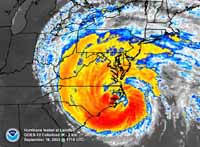

| Hurricane

Isabel slams the North Carolina coast in this enhanced

infra-red GEOS-12 satellite image from NOAA. |

When

nature gathers its humbling might into monstrous storms

and punishes these shores with a vengeance that makes

man flee in fear, the sand gives way under the onslaught.

Like a Willow in the wind, this flexibility allows the

Outer Banks to hold its own against the oceans unrelenting

fist.

Hurricanes, tropical storms and

"nor'easters" can drastically accelerate this sand movement.

The high water can eat away at the protective beach dunes,

or wash them completely away, or rapidly fill an existing

inlet with sand. Dramatic changes such as these that would

normally take years, decades or even centuries to happen,

can occur in only a matter of hours in one of these storms.

And sometimes, usually only once in a lifetime, a storm

will even slice a new inlet across the barrier islands

just as quickly.

|

|

This

USGS aerial photo was taken just

3 days after Isabel created the new inlet. |

Inlets

Come And Go:

The Case of Isabel Inlet-

Hurricane Isabel reached the status

of a category

5 monster, as bad as they come, but weakened to a

category 2 by the time it pounded the Outer Banks in the

middle of September of 2003. Even as a category 2, its

rain and hail and wind caused havoc far into the piedmont

of North Carolina as it cut northwest across

the northeastern end of the state. Power outages persisted

for days, even so far from the center of Isabel's destruction

as Alamance and Guilford counties, and points west. The

Outer Banks from Carova and points inland, all the way

southward to Cape Lookout, suffered extensive damage.

On September 18th, within a matter of hours, a new inlet

was cut across Hatteras Island, severing the southern

end of the island.

|

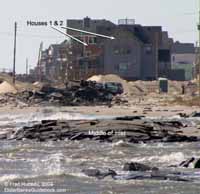

| This

telephoto image by the author shows a close-up of

the building that washed into the sound. |

The oblique

aerial photo from the USGS (above right) and this

overhead

aerial photo from NOAA at left show two bird's-eye

views of the newly created inlet, located between the

villages of Frisco and Hatteras. (The location can be

found on the Coastal

Guide Map.) Dunes, power lines, utility pipes and

a section of NC Hwy. 12 were completely swept away here.

Oceanfront buildings were demolished or carried away by

the high water. One building can be seen where it came

to rest in the sound, visible in the USGS

photo as a small white rectangle to the right of the

label "Sound".

The oblique

aerial photo from the USGS (above right) and this

overhead

aerial photo from NOAA at left show two bird's-eye

views of the newly created inlet, located between the

villages of Frisco and Hatteras. (The location can be

found on the Coastal

Guide Map.) Dunes, power lines, utility pipes and

a section of NC Hwy. 12 were completely swept away here.

Oceanfront buildings were demolished or carried away by

the high water. One building can be seen where it came

to rest in the sound, visible in the USGS

photo as a small white rectangle to the right of the

label "Sound".

This detail section from the USGS aerial photo

farther above is labeled to provide visual orientation

with the other photos below. |

Compare this ground-level photo (looking southward

from the Frisco side of the inlet) with the detail

photo above. The "foreshortening" affect of the

telephoto lens makes the buildings look much closer

to the inlet than they really are. |

The

new inlet was dubbed "Isabel Inlet". Since the ferry dock

is located at the south end of Hatteras village, it could

not be reached. Road damage, bridge damage and building

debris in the village added to the problem. Even the Ocracoke

end of the Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry crossing was closed

down because Hwy. 12 was damaged so badly the ferry docks

there could not be reached from Ocracoke village. Though

Ocracoke village could still receive supplies by regular

ferry from Cedar Island and Swan Quarter, only a small

passenger shuttle ferry was available for Hatteras village,

and it was limited to residents and emergency personnel.

|

| Old

and young alike walked the mile from Frisco Pier

to the new inlet to see what Isabel had done. |

Non-residents

were not allowed onto the Outer Banks for two weeks after

Isabel because much of Highway 12 was covered in a deep

layer of sand and the pavement was damaged or washed out

in many places. Much storm debris had to be removed as

well. But once visitors were again allowed access, many

came to see this natural wonder, the new inlet, which

had sliced off the southern end of Hatteras Island. Vehicles

could only reach as far south as the Frisco pier on the

south side of Frisco. From there it was a mile

walk down Hwy. 12 to reach the inlet. |

|

| The

author at Isabel Inlet. |

|

| Wide

angle view of Isabel Inlet from ground level. |

Standing

at the edge

of Isabel Inlet on the centerline of a shattered and

jumbled Hwy. 12 was an eye-opening experience. Crumbled

asphalt lead right into the ocean where the highway had

been only days before. Looking across to Hatteras Village,

the two

small "islands" remaining in the middle of the inlet

were covered with crumbled asphalt, evidence that the

highway had previously crossed there. At right another

photo plainly shows a turquoise pipe and a large black

"spiral" pipe which carried utilities, now ripped

apart and uncovered by the storm. Standing

at the edge

of Isabel Inlet on the centerline of a shattered and

jumbled Hwy. 12 was an eye-opening experience. Crumbled

asphalt lead right into the ocean where the highway had

been only days before. Looking across to Hatteras Village,

the two

small "islands" remaining in the middle of the inlet

were covered with crumbled asphalt, evidence that the

highway had previously crossed there. At right another

photo plainly shows a turquoise pipe and a large black

"spiral" pipe which carried utilities, now ripped

apart and uncovered by the storm.

Even though the power poles had

already been replaced by the time Hatteras Island was

opened again to visitors, services to the isolated and

devastated Hatteras village still were not restored. There

was too much damage to the infrastructure and buildings

to allow power back on (more about the structural damage

in Hatteras Village is covered ahead on page 2).

The inlet itself was closed in November

of 2003 by filling it with dredged sand, and the missing

section of Highway 12 was replaced. Highway 12 and Hatteras

Village finally opened to general public access on November

22, and the normal ferry schedule resumed between Ocracoke

and Hatteras at noon on that same day. |

|

| Another

view of Isabel Inlet. |

The Isabel Breach-

|

| The

breach between Hatteras village and Hatteras Inlet

is shown in this aerial photo from NOAA. |

The

dramatic creation of Isabel Inlet north of Hatteras village

got all the "press", but Hurricane Isabel nearly created

a second inlet on the south side of Hatteras village as

well. This second location received little mention in

the news. It is, however, a perfect example of what is

called a "breach". This happens when a storm creates a

wash across the barrier island that is only deep enough

for high tide or wave surges to wash across, but too shallow

for a constant flow of water.

|

| The

breach, after it was filled with dredged sand, viewed

from the sound side on the Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry. |

|

| This

telephoto version of the above photo shows waves

are still visible over the sand-filled breach. |

The

NOAA aerial photo above clearly shows the

breach. Sand and vegetation on the sound side of the

island is washed away creating a notch on the sound side

which did not fully cut across to the ocean. The ocean

side of the breach is dark and wet where waves break across

it. Left to nature, such a breach may fill in naturally,

or instead may continue to erode away until it too becomes

a small inlet.

|

| Isabel

Breach after it was filled in, viewed from the beach

looking toward the sound. (N 35.20028 W 075.71608) |

Unlike Isabel Inlet, this breach

had little impact on residents or visitors, since it was

situated south of Hatteras village, where there are no

roads or buildings. The only access to this area is by

4WD along the ocean beach (Ramp

#55), which is the path used to reach the extreme

southern tip of the island at Hatteras Inlet where fishing

is a popular activity. An inlet here would only cut off

4WD access to the area for fishing. Still, authorities

chose to fill the breach with dredge sand. The wide angle

and telephoto images at right, taken from the Hatteras-Ocracoke

ferry, show the area of the breach from the sound side

after

it was filled in. In the telephoto shot waves

can clearly be seen across the sand on the ocean side.

From this it becomes obvious the land is not very high

here. The absence of high beach dunes, which would normally

block such a view, leaves the area vulnerable to future

storms. |

The

Case of New Inlet, Pea Island-

The Pier in the Marsh

Smack

in the middle of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge,

at mile marker 34 (GPS coordinates N

35.67510 W 075.48084) on Hwy.

NC 12 is a strange sight. What looks to be a very long

pier sits

in the shallow marsh. It is a curiosity for certain,

as there would seem to be no logical reason for a great

long pier to be there. Smack

in the middle of Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge,

at mile marker 34 (GPS coordinates N

35.67510 W 075.48084) on Hwy.

NC 12 is a strange sight. What looks to be a very long

pier sits

in the shallow marsh. It is a curiosity for certain,

as there would seem to be no logical reason for a great

long pier to be there.

This old "pier" is in actuality

an old bridge. This area of Pea Island is still known

as "New Inlet", and it clearly exemplifies the dynamic

nature of the Outer Banks. This was one of those inlets

that came and went, more than once. Though the name "New

Inlet" has often been applied to other inlets which appeared

along these barrier islands, this particular "New Inlet"

appeared north of Chicamacomico (Rodanthe area) sometime

in the 1730's. It was always fairly unstable, partially

filling, then widening again in cycles through the decades.

Then, close to 200 years later, in 1922, it closed completely.

This old "pier" is in actuality

an old bridge. This area of Pea Island is still known

as "New Inlet", and it clearly exemplifies the dynamic

nature of the Outer Banks. This was one of those inlets

that came and went, more than once. Though the name "New

Inlet" has often been applied to other inlets which appeared

along these barrier islands, this particular "New Inlet"

appeared north of Chicamacomico (Rodanthe area) sometime

in the 1730's. It was always fairly unstable, partially

filling, then widening again in cycles through the decades.

Then, close to 200 years later, in 1922, it closed completely.

But just eleven years later, in

the fall of 1933, hurricanes again opened the inlet, cutting

two channels across the very center of what is now Pea

Island National Wildlife Refuge. Though there was no Hwy.

12 or any other actual road along these islands south

of Oregon Inlet prior to the end of World War II, this

was the era when the "motor car" was beginning to make

itself useful as a means of transportation via the beaches.

But passage along the beachfront, or elsewhere on the

islands for that matter, still required a means to cross

the inlets. These newly cut channels were narrow and lent

themselves to being bridged, unlike the wider inlets,

which made a ferry more economically practical than bridge

building. So two wooden bridges were constructed across

the inlet channels, only to see the inlet close once again

soon after the bridges were put into operation.

But just eleven years later, in

the fall of 1933, hurricanes again opened the inlet, cutting

two channels across the very center of what is now Pea

Island National Wildlife Refuge. Though there was no Hwy.

12 or any other actual road along these islands south

of Oregon Inlet prior to the end of World War II, this

was the era when the "motor car" was beginning to make

itself useful as a means of transportation via the beaches.

But passage along the beachfront, or elsewhere on the

islands for that matter, still required a means to cross

the inlets. These newly cut channels were narrow and lent

themselves to being bridged, unlike the wider inlets,

which made a ferry more economically practical than bridge

building. So two wooden bridges were constructed across

the inlet channels, only to see the inlet close once again

soon after the bridges were put into operation.

Today the remnants of these old

wooden bridges attest to the inlet's existence, looking

curiously out of place across the marsh grasses of Pea

Island. One of these bridges is still recognizable, shown

in the telephoto

view at right above. The other bridge is now marked

only by rows of pilings, which can be noted in the aerial

photos below.

|

| This

composite detail better shows the bridge remains. |

|

| Two

aerial photos from NOAA were composited to created

this image of the Pea Island "New Inlet" area. |

The

composited aerial

photo from NOAA at left, and a close-up

of the same composite at right, clearly show the former

path of the road as it swung away from the beach and crossed

the two bridges, then swung back toward the beach again.

The south bridge (left in the photos) is now only a line

of pilings, but enough of the north bridge (right in the

photos) remains that it is easily visible from Hwy. 12.

Next, see what can happen to beach

dunes, even if they're two stories high, and marvel at

an ancient forest in the surf. |

|